What are the odds?

The story behind the placement of a historical marker for the 1889 Thaxton Train Wreck

Chunks of granite lay strewn about the intersection of 8th Street, North Ocoee, and Broad Street in Cleveland, Tennessee. A crumpled vehicle rested against the base of a memorial monument, the driver unharmed but an obelisk which had stood over twelve feet tall was split in two. The entire top shaft, shaped like a miniature Washington Monument, rested on the ground near the base of the marker. The citizens of Cleveland had erected the monument in honor of three prominent citizens who perished in an 1889 Virginia train wreck.

Now, nearly 124 years after the memorial had been placed, another prominent citizen stood at the site and gazed at the damaged monument. His name was Allan Jones (no relation), a successful businessman and lifelong resident of Cleveland. Beyond his personal interest in the history of his hometown, Jones had a special connection to the monument. He had just purchased America’s oldest tailor-made clothing company, Hardwick Clothes, which was founded by a man named Christopher Hardwick in 1880. One of the names inscribed on the shattered monument was John Hardwick, a victim in the wreck at Thaxton and son of Christopher Hardwick.

One month later, in May of 2014, my phone rang. I was at a beach vacation rental with my family. We were staying at the same place I had been three years earlier, when I had decided I would write a book to memorialize the lives lost and long forgotten at Thaxton. The caller was Allan Jones.

Mr. Jones had searched online and found my book, Lost at Thaxton. He wanted to learn more about the location of the wreck at Thaxton so that he could visit the site. I explained how he could access the site by pulling off the shoulder of the highway, but there wasn’t anything to mark the location. I offered to send him a map link to show the spot. He was surprised to hear that there wasn’t any type of marker at the site.

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources sets the criteria and approval process for historical highway markers, but the not-so-trivial cost of manufacturing and placing the marker requires a sponsor to pay for it. I mentioned that I hoped to get a marker at the site and I had considered starting a crowdfunding campaign to raise the money. I took a sip of lemonade just as Mr. Jones began to reply.

“I’d like to pay for that,” he said.

After I wiped the lemonade from my laptop screen, I thanked Mr. Jones for his offer to fund a marker and went straight to work with his team at the Allan Jones Foundation to get the ball rolling. The Virginia Board of Historic Resources only reviewed marker applications at its quarterly meetings and we wanted to get the marker approved and installed as soon as possible. My call with Mr. Jones was on May 27, and the deadline to file the application for the next board meeting was June 1. I knew I was going to be busy with sandcastle construction projects with my kids during the day, so I happily prepared to burn the midnight oil once again.

I drafted text for the marker, completed the VDHR application, and put together some map images for a possible location. The folks at the Allan Jones Foundation began to reach out to their contacts in Virginia, and after dotting the I’s, crossing the T’s and crossing the fingers, we submitted the application on May 30, 2014 to Jennifer Loux at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. She would put the finishing touches on the proposal, and then we would have to play the waiting game until the Board of Historic Resources decided in September.

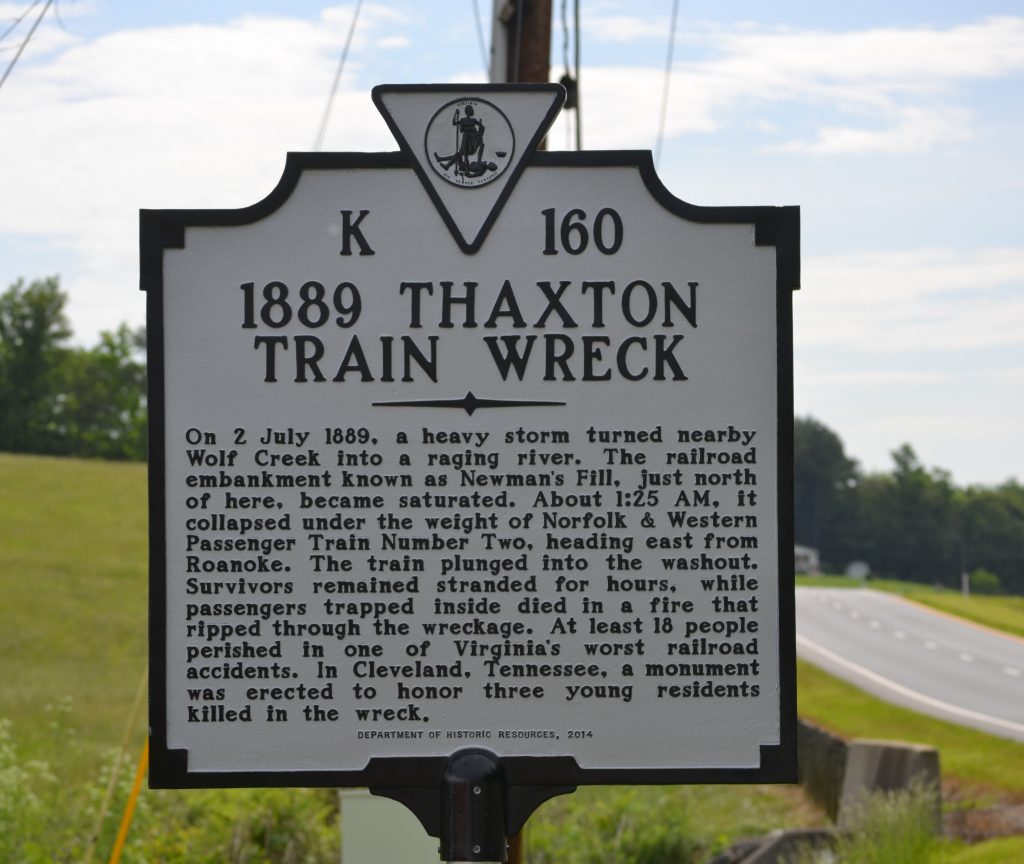

I received word from Jennifer Loux on September 18, 2014. The historical marker had been approved. Finally, the horrible wreck at Thaxton, one of the worst in Virginia history, would have a permanent marker to commemorate the site and honor the memory of those lost on that terrible night in 1889. It was the most awesome email I had ever received.

While we waited for the Virginia Department of Transportation to survey the site, approve the final location for the marker, and for the Sewah Studios foundry in Pennsylvania to build and ship the marker, we could keep ourselves busy with preparations for a dedication ceremony, scheduled to take place about eight months later.

…

On the morning of July 3, 1889, one day after the wreck, Christopher Hardwick and Samuel Marshall were desperately scouring the wreckage at Thaxton for the remains of their sons. Marshall had offered $1,000 to anyone who could help him find his son Will’s body. After searching for the entire day and finding nothing, the men prepared to take a sorrowful trip home. Hardwick sent a telegram ahead of their departure. “Our last hopes gone. Have been to the wreck and find no trace of the boys.”

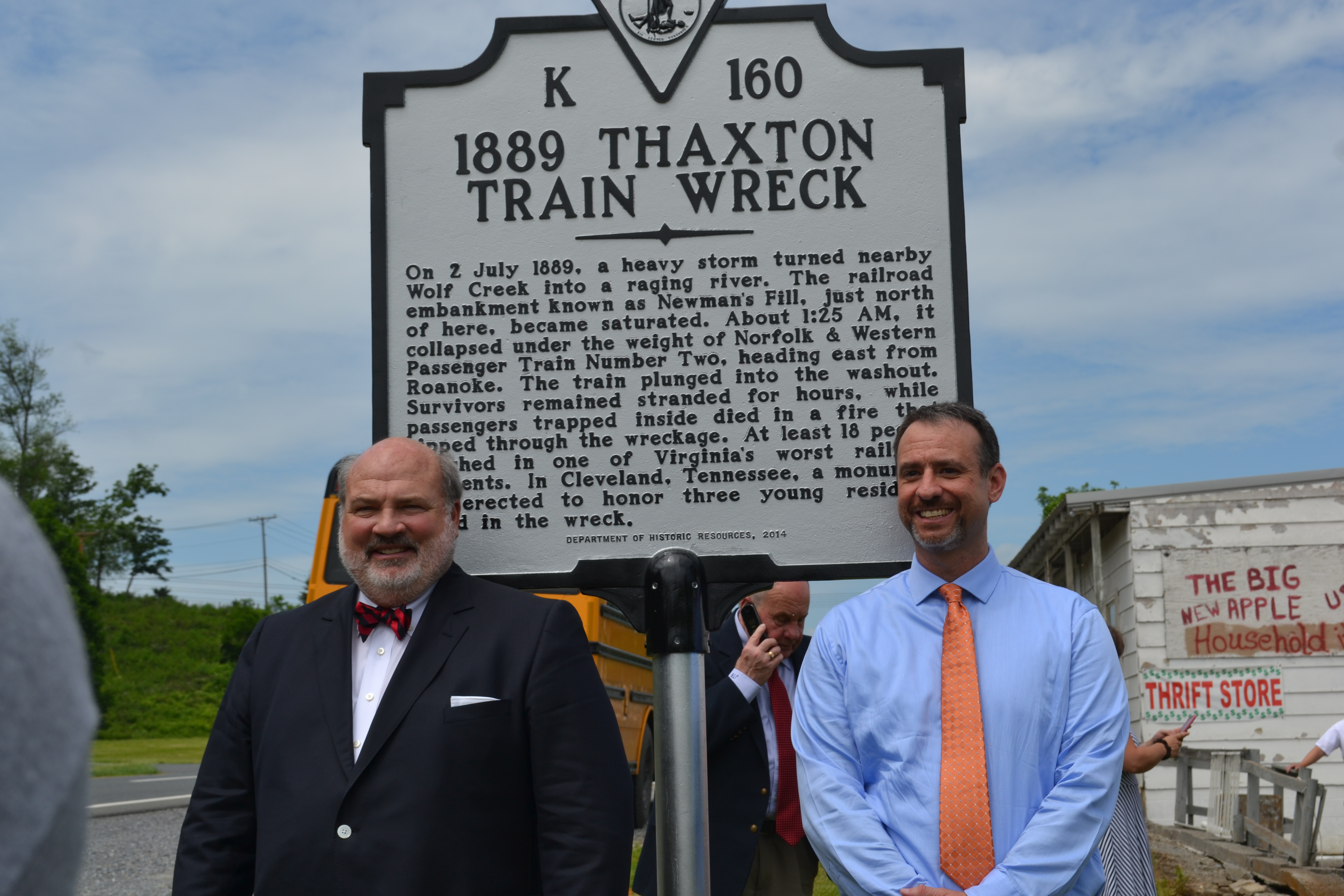

On May 19, 2015, perhaps for the first time since Hardwick and Marshall had searched for their sons in the debris of passenger train Number Two, a group of citizens from Cleveland, Tennessee arrived at Wolf Creek in Thaxton, Virginia. The group included Allan Jones and his sons, Cleveland Mayor Tom Rowland, Cleveland historians Debbie and Ron Moore, Debbie Riggs, author of a book about the wreck’s impact on Cleveland titled The Day Cleveland Cried, and Tommy Hopper, the great-nephew of wreck victim John Hardwick.

This time the visitors from Cleveland came for a moment of celebration, the dedication of the historical marker to commemorate the 1889 Thaxton Train Wreck. No longer would there be “no trace of the boys” at the wreck site as Christopher Hardwick had said in his somber telegram. The marker would serve as a permanent remembrance at the spot where the young men from Cleveland and fifteen others took their final breaths.

We gathered together beneath a tent just a few yards away from the same tranquil creek which had morphed into a raging river and washed away the railroad tracks all those years ago. The Allan Jones Foundation had handled all the arrangements for the ceremony, and along with the folks from Cleveland, several Thaxton residents, railroad history buffs, local media, and a group of Thaxton Elementary School students attended the dedication.

During the ceremony, I had the honor of reading aloud the eighteen names of those who had lost their lives in the wreck at Thaxton. It was something I had hoped to do since the early beginnings of my research for the wreck and a moment I will never forget.

After some words from Mayor Tom Rowland, Allan Jones provided some background on how he got involved in the process. He thanked many of the people on his team who had helped to get the marker in place and coordinate the dedication ceremony. He expressed how proud he was to play a part in getting a marker at the site, and how important the history of the wreck is to Thaxton and the importance of the site to the whole state of Virginia. After he finished, we listened to a beautiful rendition of Amazing Grace played on the bagpipes by Major Burt Mitchell.

The ceremony finished with a closing prayer from Randy Martin, pastor of Cleveland’s Broad Street United Methodist, the same church where Christopher Hardwick had once worshiped. Just as Pastor Martin finished his prayer, a Norfolk Southern freight train eased by our gathering on the very same route that had once carried passenger train Number Two to that fateful place.

It was like a Hollywood ending to a story that began 126 years earlier with a terrible crash and the horrific deaths of eighteen men, women, and children. Some of their remains were buried together in an unmarked grave in the city of Roanoke, while many of their bodies were never found, consumed by the flames in the aftermath of the wreck. The wreck and those who perished were mostly forgotten, until a confluence of chance circumstances led to that moment. A permanent marker unveiled to memorialize them all as a train passed by on a warm spring day.

But will that truly be the final scene, or might another Hollywood ending someday complete their story?

When I started the research for Lost at Thaxton, I had three primary goals. First, I wanted to tell the story of the Thaxton train wreck as true to the details as I could. The story had never been told in its entirety, and I wanted to write an accurate and compelling narrative that honored the people who lived and died that night while documenting the history to the best of my ability.

Second, I hoped that at least twenty people (not including my awesome family members), would read the book. The book is in several libraries now in a few states, carried by a few museums and gift shops, and I am happy to report that it passed the twenty-reader threshold some time ago now. The feedback from those readers seems to indicate I might have done okay with the first goal as well.

I had set my third goal to get a historical marker placed at the site. I thought that would take a bit longer to raise the funds and there was no guarantee we could get approval. An unfortunate collision with a Cleveland monument honoring three of the lives lost at Thaxton set off a chain reaction, resulting in a memorial to all eighteen of those who perished. Thanks to Allan Jones and his team, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, and the grace of God, we had a marker at the site in less than two years after the book was released.

As I did my research, I began to think about a fourth goal, one much more improbable than the first three and even more unlikely to be achieved. I thought about the drama of everything that happened that terrible night: the compelling stories behind each person on the train, the gut-wrenching emotions, the scale of the natural disaster, the individual heroics in the immediate aftermath, the harrowing hours the passengers spent stranded until nearly daybreak, the corporate interference and heartbreaking searches for missing loved ones in the days afterward. It has all the makings of an amazing movie. How many people would learn the names of those who had lost their lives and long been forgotten if this story were told on the big screen?

I pictured scenes in the movie, actors and actresses who would be great to play certain people on the train, and I even made a list of songs that would be great for the soundtrack, including one particular song by Sarah Jarosz that came to me over and over again as I wrote the book. I could hear that song playing just as the closing credits roll, a camera mounted near the front of a steam engine winding through the mountains while the credits scroll by.

The odds of a movie getting made are slimmer than a penny that has been crushed beneath the wheels of a massive steam locomotive, but who knows? What are the odds that someone would collide with a monument honoring the three Cleveland men who lost their lives at Thaxton? The monument stands at a busy intersection, but I believe it had never been hit in its 124-year history. What are the odds that the man who had just purchased Hardwick Clothes, the company founded by the father of one of the wreck victims, would be close by, get a call about the toppled monument, and hurry over to take a look? What are the odds that he would then begin to research the wreck online and find a book written by another Jones which had been released only seven months earlier? What are the odds that he would call me while I was at the very same beach rental where I had first learned about the wreck and decided I would write a book about it? What are the odds that one Jones would offer to fund the historical marker at Thaxton, after talking to another Jones who had written a book about the wreck and was the great-great grandson of yet another Jones who had overseen the tracks at Thaxton?

Given the commonality of the name Jones, I suppose that last one isn’t so rare. I still have my eye on that fourth goal. We haven’t had a chance to visit that beach rental since I got the call from Allan Jones that set the marker process in motion. It may be time to schedule a little trip, and maybe I’ll get a call from a Hollywood history buff who wants to bring the story to life on the big screen, like Kevin Costner or Tom Hanks. What are the odds?

If you’d like to visit the historical marker, this Google Maps link will take you to the general location where you can pull off the road at the marker.